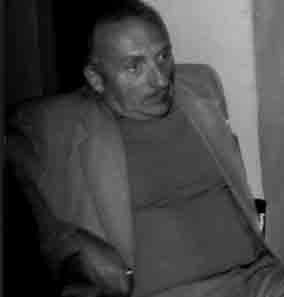

The person to whom the centre is entitled: his life, his engagement

On 24th January 1984 Domenico Sereno Regis died in Turin, his city. The name of Domenico is still vividly alive in the memory of many people, not only in Turin, and not only between those who met him in person, because his passage between us, so short and intense, left many traces such as the “study and documentation Centre about peace, participation and development’s problems”, which he helped to create and which took his name.

On 24th January 1984 Domenico Sereno Regis died in Turin, his city. The name of Domenico is still vividly alive in the memory of many people, not only in Turin, and not only between those who met him in person, because his passage between us, so short and intense, left many traces such as the “study and documentation Centre about peace, participation and development’s problems”, which he helped to create and which took his name.

Today the center is one of the most solid and qualified national points of reference for the composite area which makes reference to nonviolence peace research. We can’t set about writing his short and essential profile without starting from the memories that we have from him, still clear and precise, even if at a distance, at this point, of years.

Two, in particular, are the images standing in front of us, when we think about Domenico. The first one is the one of a sweaty face, of a tired body in contrast to a witty and ironic spirit, near the arrival of a Perugia-Assisi Marche for Peace, close to S. Maria degli Angeli. We left Turin in 9, on a friend’s van, to participate in one of the first reboots of the march for peace, during the ’70s, and Domenico was with us.

He was older than us, but he wanted to cover the 30 km, separating Perugia from Assisi, up to the stronghold, trying to alleviate the effort in the last strenuous steps with cheerful self-irony. We could say that this image is almost an emblem of his effort of man “on the road”, , (‘’My job was walking. I attended up to three meetings per evening in order to connect, to report the activities one to the other’’); we don’t know the reason why we spontaneously associate this image to one of the last memories we have of him: Domenico, suffering in bed in his house in C.so Inghilterra, aware of struggling an unequal fight against the disease, but who continues to inform himself about what is being done, to propose, to worry about how to face an obligation, to ‘’live’’, like he had always done. That was Domenico Sereno Regis.

We searched, through the testimonies (memories) of those who met him, the ways to describe him, to talk about him: a “politician without power”, a “fighter without violence”, a “heckler of the quiet living”, an “innate protester”, an “amazing volcano”, a “worker of the international justice”, an “inspirer of grass root democracy”, a “free spirit”, a “believer”, a “ nonviolent partisan’’. We could start from this last definition of a ‘’nonviolent partisan’’ in order to talk about Domenico’s life and his passionate, multifaceted and even paradoxical engagement . How can you be a nonviolent partisan?

You can, if you deeply support the choice of the liberation’s fight and so you feel the civil and political duty to join the partisan formations, but at the same time you can’t silence the ethical imperative of “Thou shalt not kill” and so you search for the ways of an unarmed resistance .

Through this way Domenico Sereno Regis arrived to nonviolence.

Born in Turin on 7th December 1921, he joined the Resistance in his early 20s; immediately after the war, from 1945 to 1947, he was the president of “Gioventù Operaia Cristiana (GiOC – Christian Working Youth) and after that he was one of the promoters of the groups “Amici di don Mazzolari”, and he collaborated with the magazine “Adesso” and he got in touch with French magazines “Esprit” and “Témoignage Chrétien”. This journey clearly outlines the foundations of his engagement: a solid reference to the evangelic message and a free and fighting religious spirit.

Meeting the International Fellowship of Reconciliation (IFOR) was then completely natural. This movement was created in England in 1914, at the outbreak of the First World War, by some English and German christians, who were imprisoned during the War for their conscientious objection. In 1919 the movement extended worldwide. The MIR (Movimento Internazionale della Riconciliazione) was created in 1952 by waldensian pastors Tullio Vinay and Carlo Lupo and by some Quakers as the Italian section of IFOR.

In the policy card it can be read that “the MIR re-unites as members all those who believe that the love manifested by Jesus is the only force that can defeat the evil” and who commit to “refusing every preparation and participation in the war”, to “building peace, which is the result of love, removing with the nonviolence method, every cause of war and conflicts, such as the social injustices, the hunger, the racial and ideological discriminations”.

In MIR Domenico Sereno Regis found the way to conciliate his engagement as a believer and his civil passion, which was expressed in thousand ways, but which always had as focal point his vocation for peace, in terms of fair relationships, refusal of war and violence, opening, dialog and exercise of grass root power. In 1967 he became member of MIR National Council, for some years he played the role of national vice-president of the movement and in 1980 he became its president.

Between the end of the ‘60s and the beginning of ‘70s the strongest effort was the legal recognition of the conscientious objection, effort which caused to Domenico accusations of ‘’contempt to the armed forces and instigator of militaries to disobey laws’’, followed by trials during which he claimed constantly the right-duty which every citizen has to obey firstly to his own conscience, when the laws of the State are in contrast to it. In 1972 was finally approved the law permitting conscientious objection to military service; it was necessary to fight to actuate it, defeating the resistances which were still obstructing a full application.

MIR stipulated a convention with the defense minister for the assignation of the conscientious objectors in civil service at their headquarters. Domenico, who was the responsible, worked hard at the Coordinamento Enti di Servizio Civile (CESC – Civil Service Bodies Coordinating Committee), to improve and qualify the organization of the young objectors’ service in the various bodies and to create connections in order to more effectively support the service towards the Defense Department . However, according to Domenico, conscientious objection should not be addressed to the military service only, but also to other forms of cooperation with the military, such as, for example, the production of weapons and the military expenses. In this way, he sustained the first forms of objection to the work in the military industry and he contributed to promote the organization of the conscientious objection campaign to military expenses. Furthermore, his effective and daily engagement for peace didn’t take place only in the Nation, but it had an international dimension.

He participated in international conventions, like meetings for peace in Prague or those of the Berliner Konferenz in East Berlin and in Budapest; he had met some nonviolent leaders like Jean Goss, president of the international IFOR, Jean Marie Muller, founder of the Mouvement pour une alternative non violente, or the Nobel price for peace Adolfo Perez Esquivel, representative for the Argentinian IFOR, persecuted by the colonels’ dictatorship ad animator of “Sevicio paz y justicia” (SER.PA.J).

All of them came to Italy in many occasions, Jean Goss held a conference in Turin organized by Domenico Sereno Regis, as early as in April 1963, at the origins of the movement for peace in Italy (Aldo Capitini had organized the first march for peace Perugia Assisi in 1961).

In the hardest phase of the fight for peace, the one against the Pershing and Cruisemissiles , which saw the growth of a strong antinuclear movement all over Europe, Domenico went with his wife to Comiso, in order to sustain the pacifists engaged in blockades of the missile central.

His widespread effort was also naturally expressed against civil uses of nuclear energy, of which he found the limits, the risks and the connections with the military-industrial system. In parallel he also conducted an effective and constructive action, with the passionate research of bottom-uo / grass root participation forms, which could substantiate democracy. “Participated democracy” is an expression which you can often find in “Controcittà”, the journal of the spontaneous District Committees in Turin. .

You cannot think about the social orientation centers, local assemblies of citizens’ debate and self-management, created by Capitini during the second After-war: the nonviolent culture was looking, at first with Capitini and then with Sereno Regis, for the forms of a real grass root power, in which an active citizenship and a political participation, in terms of passion and of service, could be expressed.

But this tireless activity was not naively optimistic, neither unprepared; an inflexible hope, joined to a “rational pessimism”, supported his engagement and made it so practical and noble . He knew he was, in the short period, a lawyer of lost cases, he knew he was a minority man, not part of the elite, but he didn’t worry about little numbers; he persisted in the path of active nonviolence with resolution and tenancy, because he knew it was the only viable. Domenico Sereno Regis, a man mainly of action, didn’t leave many writings.

In the short text that follows, taken from an intervention he made in a conference in Genoa about the nonviolent popular defense, talking about the experience of spontaneous district committees in Turin in the terrorism years , he effectively expressed his conception of nonviolence and nonviolents’ role: “We always realized later on that in some committees there were citizens, who could be defined as nonviolent.

As far as we are concerned, their characteristic was never underlined, because there weren’t any differences on goals and methods of struggle with other citizens. Explicit solidarity declarations of the districts’ movement were not missing, for example in occasion of the trial, in which many citizens were involved and accused of contempt of Armed Forces, guilty only of claiming old military areas and structures to be used for civil purposes (…) A grass roots, basically nonviolent politcs, which works for a substantial transformation of society, gains a particular meaning in a city like Turin where, because of the dramatic social disorders described in the first part, almost like for a logical consequence, is in action a clash is occurring between armed revolutionaries, FIAT and the economic power, the State with its civil and military structures.

The responses to made-to-order murders and wounding are selective dismissals, hiring filtering and blocking, and the threat of closing factories, political and psychological counter-terrorism and the militarization of the city. In this “escalation game” of violence which the involved parts tend to use for their respective purposes of chaos, patronal revenge, reinforcement of central power, the grass roots movements rejected provocations, sometimes arriving from different parts, and insisted on the necessity of proposing again those structural and constructive initiatives (judiciary, police and jails’ reform, State reform through an effective decentralization, citizen information and formation to the responsibility starting from school etc.), which are the bases in order to realize a new, equilibrate, livable, people-orientated, unarmed, participated and, prospectively, nonviolent society.

Capitini in Perugia had already proposed, in the years of postwar chaos, an action of capillary political growth based on those spontaneous committees, which were the “Centri di Orientamento Sociale (COS – Social Orientation Centers)”, which should havegradually transformed State structures in a nonviolent sense, but without result. And with him many other unheard prophets! This is the story of a past, that we have not to fear”. In the text there is all the practical philosophy of Domenico: being few people “shouldn’t frighten us”; between violence and repression there is a third way which is the strenuous and long construction of a “new, equilibrate, livable, people-orientated, unarmed, participated and, prospectively, nonviolent society”; the of nonviolents role is staying behind the transformation processes, operating in the basic reality they belong to, having as reference the “unheard prophets”, who were able to indicate the ways we have to go.

Joining the concrete and real dimension of problems with a high and forward-looking perspective. Acting locally and thinking globally is what Domenico Sereno Regis practiced in all his short, but intense life.